History of the Jacob Hochstetler Family

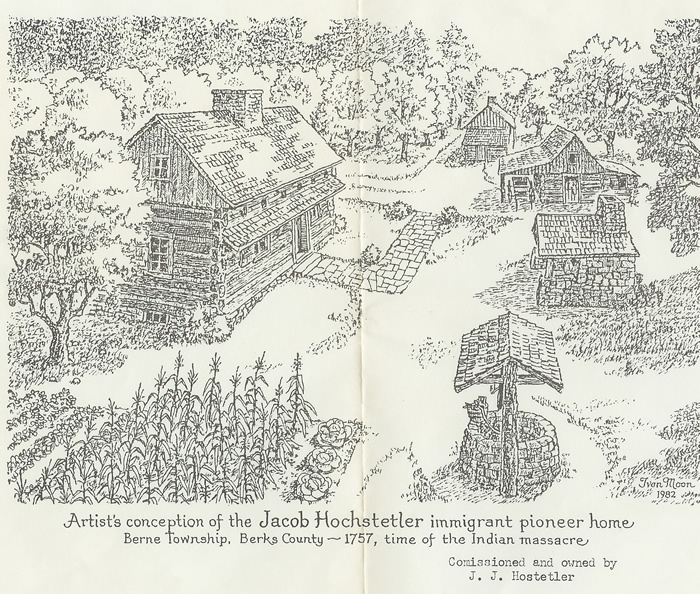

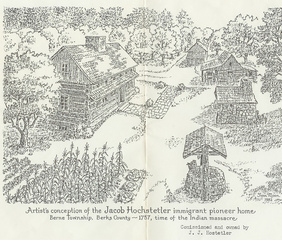

Historical Overview Hochstetler family farm before the attack

This account is adapted from the historical introduction by William F. Hochstetler early in the 1900s, published in The Descendents of Jacob Hochstetler (copyright © 1977 by Eli J. Hochstetler), and from Our Flesh and Blood: A Documentary History of The Jacob Hochstetler Family During the French and Indian War Period 1757—1765, 2nd ed., compiled and edited by Beth Hostetler Mark (The Jacob Hochstetler Family Association, Inc., Elkhart, Indiana, © 2003)

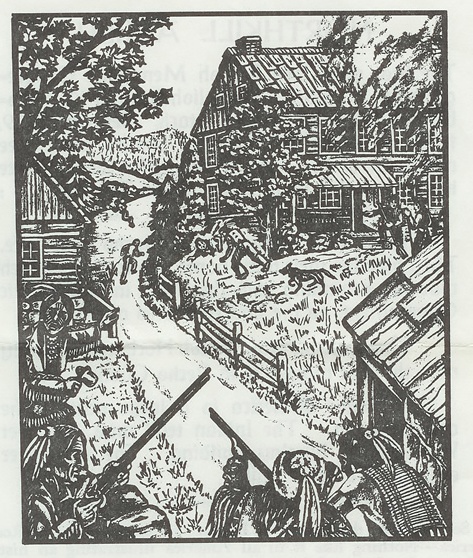

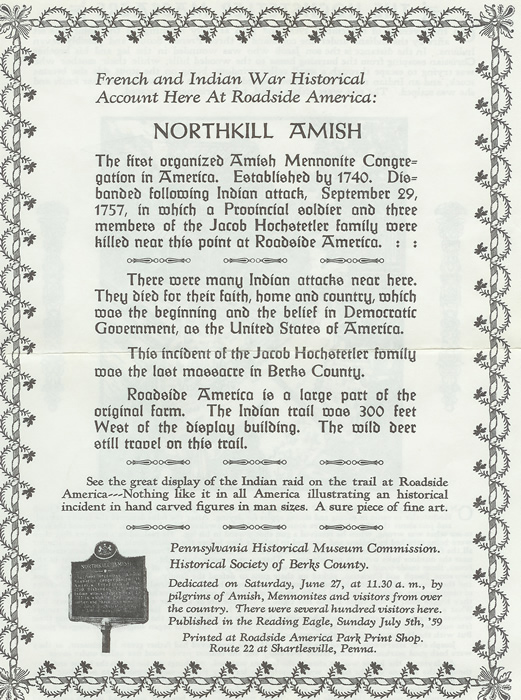

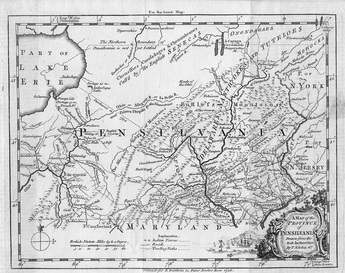

The Hochstetler family is thought to have originated near Schwarzenburg, Switzerland, perhaps in the fourteenth or fifteenth century. In the 1600s some members of the family joined the Anabaptist reform movement. Because of their adherence to the doctrines of believers’ baptism and non-resistance, Anabaptists suffered severe persecution, and beginning in the 1700s many of them immigrated to America to find religious freedom. My ancestor Jacob Hochstetler was born in 1712 in Echery near St. Marie-aux-Mines in Alsace, where his family had settled in the late 1600s. He was twenty-six years old when he arrived in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on November 9, 1738, aboard the Charming Nancy.With him were his wife, whose name is unknown, a daughter, Barbara, and a son, John, who was then three years old, and from whom I am descended. By 1739 the family had settled along the Northkill Creek on the eastern edge of the Blue Mountains in what is now Berks County, Pennsylvania, at that time the western frontier of the British colonies. They built a substantial log home and farm buildings near a spring of fresh water, cleared the land for farming, and planted several acres of fruit trees. They helped to establish the first Amish Mennonite church in America in the Northkill area the following year. During this time the Delaware Indians, or Lenni Lenape, who inhabited a large portion of Pennsylvania, lived in peace with the white settlers. They often visited my ancestors’ homestead and others throughout the area and were generally received with hospitality. The Moravians maintained an active mission to the native peoples along the borderlands, and as a result many of the Delaware became Christians. In 1754, however, the peace was shattered when France and England went to war over control of the territories west of the Appalachian Mountains. After a combined French and Indian force defeated British General Edward Braddock in 1755, many of the native tribes allied with the French and began to attack the border settlements in Pennsylvania and New York to drive the white settlers out of their ancestral lands. Between November 1756 and June 1757 several families in the Northkill area were attacked, a number of settlers were killed, and others were carried away as captives. That summer remained comparatively quiet, although a tense anxiety hung over the valley. Jacob and his wife, their sons Jacob, Joseph, Christian, and a young daughter were living in the home, while Barbara and John, who were by then married, lived on farms nearby. On the evening of September 19, 1757, the young people of the neighborhood gathered at the Hochstetler farm to help prepare apples for drying and afterward stayed for a social until late. When their guests had finally gone, the family went to bed. In the middle of the night their dog set up a clamor that roused them. Alarmed, young Jacob opened the door to look outside and was staggered when a gunshot hit him in the leg. Realizing that they were under attack, he managed to bar the door before the Indians could force their way inside. It was a moonless night and, barricaded inside the dark house, the family members could see a band of about fifteen Indians standing near the outside bake oven, evidently conferring about what to do. There were several guns and an ample supply of ammunition in the house, but in spite of Joseph and Christian's desperate pleas, their father refused to allow them to take up arms against another human being even to defend their lives in obedience to God's command not to kill. Finally, near dawn, the Indians set fire to the house. With their attackers lurking outside, the family had no choice but to take refuge in the cellar beneath their blazing home. When the fire threatened to burn through the floorboards, they staved off certain death by spraying the cider stored there on the flames. Choking on the thick smoke and scorched by the conflagration above their heads, they somehow endured until the first light of the new day. Through a small window, the strengthening light revealed the Indians filing off into the woods. Flames and smoke made it impossible to stay in the cellar any longer, and the instant their attackers were out of sight, the parents and their children began to crawl out through the narrow window. With his wounded leg, young Jacob needed help to climb through. The mother was a large woman, and it took considerable effort to drag her through the constricted opening. But at last everyone was free of the smoldering ruins. Concealed by the trees, however, a young warrior called Tom Lions had lingered in the orchard to gather some of the ripe peaches. Seeing the family emerging from the cellar, he immediately alerted the rest of his party. As the marauding band returned to surround his terrified family, Joseph outran two pursuers and hid behind a fallen tree on the hill above the house, unaware that one of the Indians had noted his hiding place. The Indians tomahawked and scalped young Jacob and his sister. Evidently motivated by a desire for revenge against the mother—legend has it that some years earlier she had refused to give them food and had driven them away—the Indians stabbed her through the heart with a butcher knife, a death they considered dishonorable. Christian was about to be tomahawked as well, but according to family tradition, he was spared because of his bright blue eyes. Dawn was just breaking when the oldest son, John, who lived on the adjoining farm, awakened to the horrifying sight of his parents’ homestead in flames, surrounded by Indians. He hastily concealed his wife and young children in a dense thicket at a distance from their house, then watched helplessly from a concealed location while the Indians prepared to carry off the survivors of the attack. Outnumbered, he could do nothing to save his family. Several neighbors ran to the edge of the meadow that surrounded the farm, but they also were helpless to intervene against the armed Indians. After taking the elder Jacob and his son Christian captive, the Indians returned to Joseph’s hiding place and took him prisoner as well. Before they were led away, the warriors allowed Jacob and his sons to pick as many ripe peaches as they could carry. Then they were forced to a rapid march across the mountains. When they arrived at an Indian village three days after the attack, Jacob saw that they would be forced to run the gauntlet. Taking his sons with him, he approached the chief and offered him the peaches they carried. The chief was so pleased by this gesture that he spared them from the cruel ordeal most captives were forced to undergo. From there, Jacob and his sons were taken on another long, exhausting march to a French fort at Presque Isle, near Erie, Pennsylvania. French soldiers from the fort gave the three captives to Indians from three different villages in northwestern Pennsylvania. Before his sons were taken away from him, Jacob pleaded with them to remember the Lord’s Prayer even if they forgot their German language. Jacob was then taken to the Seneca village of Buckaloons. Custaloga, a Delaware chief who lived most of the time in Custaloga’s Town near present-day Meadville, Pennsylvania, took one of the boys. Where the other boy was taken is unknown. According to oral tradition, Christian was initially adopted by an old Indian who died several years later, while Joseph was adopted into an Indian family. Although he pretended to be content, Jacob never grew reconciled to the natives’ life, and his captors never fully trusted him. In early May, 1758, however, he was allowed to go hunting alone and managed to escape. An arduous journey and many prayers for guidance brought him to the Susquehanna River. On the verge of starving, he built a raft and floated downstream, more dead than alive. When his raft passed Fort Augusta at present-day Shamokin, he was spotted and pulled from the river by British soldiers. Colonel James Burd took him on horseback to Fort Carlisle, Pennsylvania, a few miles south of Fort Harris, where he was interrogated by Colonel Henry Bouquet about the activities and locations of the French. Finally released, Jacob returned home. At the end of the French and Indian War, the peace treaty with the Indian tribes provided for the return of all white captives to their families. Little came of this agreement, however, and on August 13, 1762, Jacob petitioned the governor for the return of his sons. After considerable negotiations with Indian tribal leaders to secure the return of all the white captives, Joseph was returned to his father in 1763 or 1764. Christian did not come home until late summer 1765. As was common for white captives who were adopted into Indian families, both boys were initially reluctant to return to white society, especially Christian, who had been the youngest when captured, and who lived among the Indians the longest. Marrying soon after their return helped them to reintegrate into the life of their Amish community. For the rest of his life Joseph continued to regularly visit his Indian family to hunt and to join in their sports. He always maintained that if their father had allowed them to shoot at their attackers, they would have fled. Christian converted, joined the Church of the Brethren, and in time became a preacher. These courageous pioneers bequeathed to their descendants a heritage of faith that has extended through the years to me and to my children. Through my parents example, I learned to know, love, and serve my precious Savior. The tales they told of our ancestors and of their own lives inspired in me a great love of history, which God has called me to share through stories that I pray will touch my readers’ hearts and glorify God. |

Learning MoreFor more information on the Hochstetler family and on the Hochstetler Family Association, click here.

To learn more about the Mennonites, go to The Mennonite Information Center and the Swiss Mennonite Cultural and Historical Association To learn more about the Amish, go to Religious Tolerance.org For engaging and informative musings on the Amish, check out the Amish America blog. Visit the Northkill website for further information on the Hochstetler family. The Northkill Amish Series is the first full-length fictional account of our ancestors who immigrated to this country, the Indian attack and massacre during the French & Indian War, and the survivors' captivity and eventual return. |